I have a

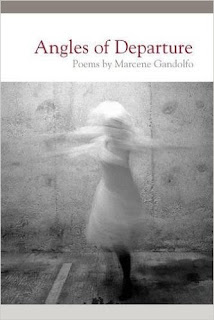

book coming out—and then I have another. Pinch me! At the age of forty-seven,

I’m late to the party, and at the party, in the corner, I’m the one wearing

sensible sneakers and asking if it’s hot in here.

It’s

typically not hot in here. I’m starting

to quit asking.

Because I

happen to be about twenty years older than my fellow emerging writers, this

shit is serious. I’m not fooling around. That first book comes out in late May,

and I’m e-mailing like a mad woman, trying to set up readings to find audiences

for my poetry. (I’m sorry, poetry—my neglected children I tardily set out to

nurture in their teenhood.)

I even put

a post on Facebook yesterday, asking anyone with a spot in a reading series to

drop me a note. I’ll do my best to drive there! I’ll work—teaching, meeting

with students, a publishing talk! I’ll sleep in my car! I’ll dine on those

little cans of Vienna sausages and packets of cheesy crackers!

Desperation

is so attractive, and such an effective marketing strategy. Still, I got some nibbles—a

few friends with programs who are interested in working something out. Even one

reading resulting from a desperate Facebook post is a good thing, and I’ll take

it. I’ll read the hell out of those poems. I’ll talk poetry with students and

let them see how magical they are for putting themselves out there and doing

such important work. I’ll fill them with a fiery hot fervor for the word.

And you

don’t have to pay me a thing.

That’s the

weird part of my offer. I don’t actually believe in bringing in writers and not

paying them. I believe in respecting the profession and the art, and in

demonstrating with my actions that poetry has value. I have coordinated

readings many times, and I have always considered it crucially important to

make every guest feel special and valued—to feed them and make them

comfortable, to not work them too hard, and to send them away with compensation

in their pocket or, more often in the university setting, on its way in the

mail.

But here I

am, offering up my services for Vienna sausages, and the Vienna sausages are

negotiable.

Ordinarily,

when I write about the writing and editing life, I’m writing from a position of

experience and knowledge. I have a set of experiences and I want to share them

with readers to give them insight into, particularly, an editor’s thinking. I

know what I’m talking about, and if I don’t, I know enough to say so in the

spirit of creating dialogue on important issues. I make mistakes and I get

carried away with the writing at times (an editor friend called me out recently

on a tremendously disrespectful phrase I included in a post, when I chastised

editors, like I often do, but included the words, “Buck up, Spunky!” Guess I

liked the assonance of the expression, but I kind of made an ass out of myself).

But I’ll go

ahead and say it—my information is typically solid, and my opinions are based

on years of experience and observation and, yes, mistakes. I think I have

something to offer on these topics.

When it

comes to setting up readings for a forthcoming book, though, I’m lost. I’m

hunting with a blunderbuss, rather than taking aim with the cool eye of a

sniper. (I’m so lost I’ve resorted to rhetoric that glorifies guns.) Maybe this

post is itself a cry for help. It’s certainly intended as a not-so-subtle plea

for invitations to read in the next year or so (Write me! karen.craigo@gmail.com ! Will work for

sausages!).

In the back

of my mind is the notion that someone needs to do something to make it easier

for reading series planners to find poets and writers. My friend Neil Aitken,

taking pity on a fool, wrote me to tell me about just such a service, one that

he recently launched called Have BookWill Travel, which links reading opportunities and writers. Expect to see

my ugly mug up there about fifteen minutes after I post this. (Neil posts

headshots. The can of Vienna sausages will be just out of frame.)

When I write my posts for Better View of the Moon, I frequently offer

advice, and while I appear to be writing it for an audience, sometimes I’m

writing it for me. It’s a way of keeping myself focused and centered. I’ve

hosted dozens of readers over the years, and I know a bit about how it goes. So

here are some thoughts on the right way to try to set up readings. Karen

Craigo, if you’re reading this, take a memo:

• Consider your value. What do

people pay writers at your career stage? (More books can mean more money.)

What’s the going rate for readings in your genre? (Fiction writers frequently

get paid more than poets, which sucks, but is nonetheless true.) What are

people paying in your area? What are they paying in the area you are targeting?

Find that information and think about where you belong on the scale.

• Bear in mind that you are trying

to set up a book tour. There is a different price point for the person who

comes asking for a reading than there is for the person a program or reading

series targets with an invitation. Sometimes, when you’re the one asking to

come, it is a good deal to receive travel, food, and accommodations in exchange

for a reading. If you’re asking to be part of a regular standing reading

series, though, you may be tacitly asking to read for the regular rate of pay.

If the reading series is in a university, there is usually a payment. If the

reading series is at a bar or bookstore, there generally is not.

• Keep in mind your purpose in

trying to set up a reading. My purpose at the moment is to get books into the

hands of readers. As this is my first book, promotion is everything. I will not

judge the success of my effort to set up readings by how much money I make;

rather, I am looking to do justice to my poems and to build my reputation as an

artist. This will undoubtedly increase my value—including my monetary value—for

the future.

• Prepare a pitch with a bio. Have

a website. Show people you approach that you are not a crazy lady—that you are

legit. Be specific about the services you can offer. An angle I have to offer

is expertise in literary journal publishing—a subject most writers are curious

about. Emphasize what you can offer to audience members, as well as services

you are willing to provide aside from the reading. (If you are ever asked to

read somewhere and to do a talk or judge a contest or meet with students, you have

the right to expect more compensation—but if you are trying to set up your own

reading, you can throw in side offers as part of the package, to sweeten the

deal.)

• Pinpoint the series you

know—ones, ideally, you have attended. (I have a reading in the fall at the

Writers Place in Kansas City—a place I know because I’ve gone to several events

there, even though Kansas City is about three hours from my home.) Contact

these series first. Then look within driving distance, because airfare drives

up the cost to whomever is paying. Pinpoint universities and longstanding

series. Go to where people are studying and writing poetry.

That’s all I’ve got. If any readers

have good advice, I could certainly use it. Please post it in the comments. I

offer you virtual Vienna sausages as a reward.